Paperback and ebook: Amazon.com, Amazon.com.au, Amazon.co.uk,

ebook: Kobo US, Kobo UK, Kobo AU, Barnes & Noble, Smashwords, Scribd, & Apple Books.

Author: Carol Ryles

Book Review: Burnt Sugar

Burnt Sugar is the first in the Never Afters Series by Kirstyn McDermott, and published by Brain Jar Press (QLD, Australia).

I’ve been a long-term fan of Kirstyn’s dark revisioned fairytales. Burnt Sugar is up there with the best. Told from the point of view of a very much older Gretel, both she and her brother Hansel carry scars from their early childhood abandonment, near death at the hands of the witch and subsequent escape. But everything isn’t as it seems. There are secrets still unanswered and a book of magic that promises old nightmares and deadly temptations. The prose is lovely and evocative, and the story grabbed me from beginning to unpredictable end.

I will definitely invest in the rest of the series.

Feature Image: Gingerbread house by Theo Crazzolara

Review of The Eternal Machine by Jemimah Brewster

Delighted to receive this wonderfully detailed review from Jemimah Brewster, editor, writer, reviewer.

The Eternal Machine is an inventive and elaborate debut novel firmly within the Steampunk sub-genre of science fiction, and Ryles has crafted a one-of-a-kind magic system that both underlies and drives the plot throughout. Balancing the elegant world-building is a rich cast of colourful characters that bring the city of Forsham and its dark workings to life. I’d recommend this book to anyone who enjoys detailed world-building, Steampunk fiction, or dark fantasy epics!

Jemimah Brewster

I’d love to post the entire review here, but it is best viewed on Jemimah’s webpage. Some of her thoughts have already given me ideas for Book 2.

The Eternal Machine is sold at:

Apple ibooks

And now on SCRIBD

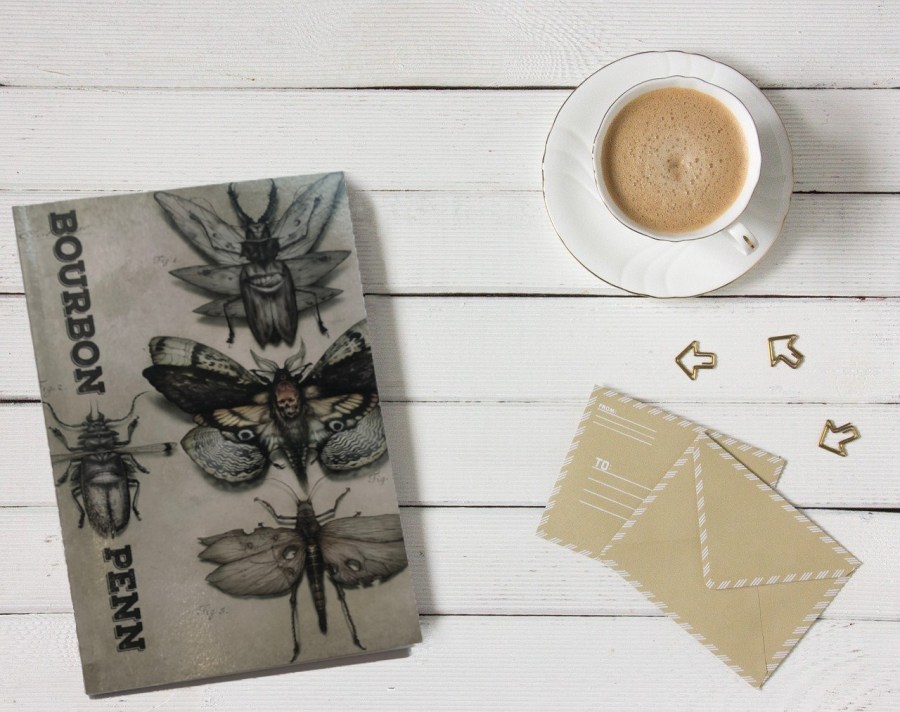

Book Review: Bourbon Penn #25

This was my introduction to the Bourbon Penn anthologies and I’m now asking myself: how has it taken me so long to discover them? At 150 pages, Issue #25 is pleasingly weird and quirky, exactly as its cover image promises.

My favourite story was Anthony Panegyres’ “Anthropopages Anonymous (AA)”, which totally nails the thoughts and actions of upwardly evolved bears. The humour is subtle and dark, while the bears’ way of thinking is a dangerous mix of animal and human.

I was particularly drawn to the mystery of Louis Evans’ “Lazaret” with its strange Twilight Zone-esque vibes; and also to the precarious balance of tragedy and creepiness in Simon Stanzas’ “That House”.

E Catherine Tobler’s “The Truth Each Carried” allows the reader to discover more than one secret through the eyes of a perceptive and gifted older woman. Her horses are wonderful!

Allie Kiri Mendelsohn’s “Mosaic” is a tale of magic told from the point of view of a very young adult. Mendelsohn’s use of language does much to enhance the characterisation and setting.

Gregory Norman Bossert’s “Appearing Nightly” is an atmospheric vignette about a magician whose performances are at once perplexing and elusive.

I finished this antho in less than a day. All six stories left me thinking about them afterwards.

Bourbon Penn #25 edited by Erik Secker is available online at Amazon, Book Depository and Bourbon Penn Website

Leanbh Pearson Reviews The Eternal Machine

The Eternal Machine launched last week 14th January, and at last I feel as if I’ve reached the first milestone of a very long fourteen-year journey. It was my first novel, one I didn’t think I would ever publish, and almost ended up in the trash basket forever. Instead, I decided to use it to work my way through the entire learning process of writing longer fiction. I used it to learn how to write character, then plot, dialogue, world building, emotion, description. At times it felt as if I were painting a picture, adding each layer at a time, making sure they not only complemented each other but also interacted. Now that it’s done, I’m glad I stuck with it. Using input I received from critters, editors, beta readers and now reviewers, the ongoing process feels like a masterclass with my own work as a focus.

I was therefore delighted to receive a review from spec fiction writer and book blogger Leanbh Pearson, who summed up her commentary with:

A new steampunk read from a debut author in the genre. Highly sophisticated world-building with combination of alternate history, steampunk and gaslamp fantasy makes this suitable for audiences of all three genres. A well-recommended read!

You can read the entire review at Leanbh’s website.

THE ETERNAL MACHINE:

ebook and paperback from Amazon US Amazon AU Amazon UK

ebook from Barnes & Noble Kobo US Kobo Au and Kobo UK

Tomorrow!

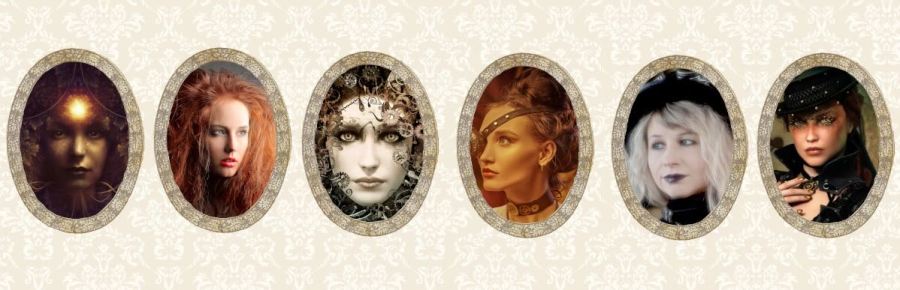

At last, The Eternal Machine will be released tomorrow, Friday 14th January! I’m excited, a little bit scared and happy to have nearly met the goal I made 14 years ago. If you like weird steampunk, gothic urban fantasy with lots of strong female characters, and a little bit of Leibniz, then this may be for you.

Edited by Amanda J Spedding and Pete Kempshall.

I must admit the scariest part was putting it up on NetGalley via BooksGoSocial a couple of months ago. But I bit the bullet and jumped in, and received an interesting mix of reader reactions, which are now on Goodreads. I took a few risks with this book by including themes that I care about and are as much a reflection of the present world as the novel’s nineteenth century setting; but that’s what a lot of steampunk is about, isn’t it? Taking risks.

Anyhow, allow me to introduce you to some of my girls.

Starting from Top Right and moving Clockwise:

1. Em is an underpaid & underemployed mechanic who dreams of being a designer, but has little chance in a city owned by industrialists; so becomes a rebel instead.

2. Solly is a resistance fighter, Em’s friend and mentor; and is a wise and natural leader.

3. Lottie is a shapeshifter trapped in the body of a human. She is wise, irreverent, witty, flippant and loves smoking cigars.

4. Phidelia is on a mission, but her unconventional behaviour has many tongues wagging against her. She ignores this narrowmindedness with all the contempt it deserves.

5. Orla is spectacularly badass and somewhat corrupted. She wants to rid the city of industrialists, but cares little about who she hurts along the way.

6. Myrtle has worked as a horologist for 24 years. She is a rebel, Em’s mentor and is fiercely protective of her younger brother who is very very tall.

Furthermore, there are also some kick-ass male characters, some good, some bad, and some a bit of both.

THE ETERNAL MACHINE: ebook and paperback from Amazon US Amazon AU Amazon UK ebook only from Barnes & Noble Kobo US Kobo Au and Kobo UK

Image Credits:

Damask Wallpaper No-longer-here

Oval Picture frame: Darkmoon_Art

Gold Rectangular Picture Frame: Aventrend

Em: Kiselev Andrey Valerevich

Solly: Atelier Sommerland

Lottie: VikkiB

Phidelia: Atelier Sommerland

Orla: Darksouls1

Myrtle: Ollyy

Images edited by Carol Ryles

Technology & Exploitation

In a recent post in Locus Online, Science Fiction is a Luddite Literature, Cory Doctorow writes about how science fiction and Luddism concern themselves with the same question: “not merely what technology does, but who it does it for and who it does it to.” In other words: “the social relations that governed its use.”

Doctorow dispels the myth that luddites fought against technology and argues that they instead opposed the exploitation of workers when automation made production of textiles faster and cheaper. It’s not hard to guess who reaped the benefits: Not the workers who manned the machines for longer and longer hours, but the wealthy industrialists who owned them.

Some would say those days are behind us. But are they? Most of our clothing comes from developing countries whose workers earn less than it costs to live. Similarly, the motor manufacturing industry in Australia has vastly shrunk for the same reasons. As a result, manufacturers and retailers enjoy higher profits and consumers buy products at a lower price.

But what about the workers? The ones whose rights have either been eroded or are nonexistent, whose efforts lead to longer hours and less pay?

Back in the 60’s my dad was a production supervisor in a big brand bread factory. He worked terrible hours starting at 2am and earned a miserly salary. Someone had told him he wasn’t allowed to join a union, but I suspect he probably could have.

We lived in a working class western Sydney suburb in a cheaply-built fibro house with a tiny mortgage, but my parents could barely make ends meet. At 40 years old, my dad was diagnosed with emphysema. Yes, he was a smoker, but he was also exposed to flour-laden air every working night, a common cause of bakers asthma. He also lost the tips of two fingers when they got caught up in the workings of one of the machines.

My grandfather fared even worse. A merchant seaman, he lost the use of his hands in a boiler accident in the 1930s. As a result, my mum grew up in poverty and was pulled out of school and sent to work as a machinist in a clothing factory at the age of fourteen. She told us some terrible stories about that!

These days, despite a few positive steps in the right direction, workers are still subjected to wage theft, unsafe conditions, wage freezes and regressive tax systems that keep many people on or below the poverty line. Meanwhile mega corporations strive for record-breaking profits.

Science fiction writers have not only been critiquing, but also predicting these kind of scenarios for decades. The movie, Metropolis (1927) is a very early example. And more recently Elysium (2013).

A notable example in books is: HG Wells’s prophetic The Sleeper Awakes (1910) where a 19th C activist is transported to the year 2100 to find the workforce is still facing oppression. Another is The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi (2009) where the world is controlled by big corporations.

Steampunk also contributes to the critique, but through a backward looking lens. One of my favourites is The Iron Dragon’s Daughter (1994) by Michael Swanwick, which begins in a factory where slaves manufacture flying dragon automatons. Another is Worldshaker (2009) by Richard Harland, where workers toil in the lower decks of a city-sized roving machine, the industrial equivalent of a Howl’s Moving Castle on wheels.

Texts such as these inspired my own novel, The Eternal Machine. As did Emile Zola’s Germinal (1885) and the many books of Charles Dickens.

The exploitation of factory workers may well have began with the Industrial Revolution, but its roots went back further than that in the medieval feudal system, and earlier still. Hundreds of years later, the injustices and inequalities continue unabated.

Feature Image by Siggy Nowak from Pixabay

For the Love of Anachronisms

Back in the computer age, people had time to read books.

Steampunk is a genre of subversion, not only due to the actions of its characters but also for the ways its writers play with reality, creating imagined histories and technologies of science and fantasy. Inspiration can be drawn from both science fictional histories and contemporary histories. For example, in Morlock Night K.W. Jeter draws on aspects of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine. In The Difference Engine William Gibson and Bruce Sterling create an alternate history where Charles Babbage’s original invention of the same name is mass produced to kickstart the age of computers.

At first sight, the anachronisms of steampunk appear to be little more than the curious gimmicks of an aesthetic that is widely believed to be over and done with. Back in 2008 when I decided to write my first novel in the genre, people would say, “Steampunk? What’s that?” Five years later when I tried to sell it, a revival had not only spiked but also petered out. The common response became, “Steampunk? Not again!” Having said that, new titles continue to be published, such as James P Blaylock’s The Steampunk Adventures of Langdon St. Ives, Gail Carriger’s Defy and Defend, and Phil Foglio & Kaja Foglio’s Agatha H and the Siege of Mechanicsburg (Girl Genius #4).

Furthermore, you can find a decent list of new works at Rising Shadow.

Perhaps another revival will happen again soon. After all, that’s how fashions roll.

But why steampunk? And why is the nineteenth century the perfect era to set it in? Is it simply a nostalgic return to the past? Or is it more than that?

Back in 2013 when I completed my PhD, I argued that steampunk was a historical narrative set in the past “seen through a speculative fictional lens that has been both irreverently tampered with and ingeniously enhanced with the benefit of hindsight.”

Similarly, Bowser and Croxall assert,

“Like most science fiction, it [steampunk] takes us out of our present moment; but instead of giving us a recognisably futuristic setting, complete with futuristic technology, steampunk provides us with anachronism: a past that is borrowing from the future or a future borrowing from the past.” (“Introduction: Industrial Evolution”. NeoVictorian Studies 3:1 2010).

In this way, the kinds of technologies that many people take for granted become defamiliarised, or in other words, the familiar is made strange and at the same time illuminated. Eric Rabkin states:

“If we know the world to which a reader escapes, then we know the world from which he comes” (The Fantastic in Literature, 1976 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977): p. 73.

The anachronisms of steampunk can also be seen as a form of subversion because they are an intentional and playful revision of accepted history. Early examples include the sentient robots of K.W. Jeter’s, Infernal Devices and the 19th Century nuclear device in Ronald W Clarke’s Queen Victoria’s Bomb. Books such as these work particularly well in a nineteenth century setting because the Victorians were similar to us in many ways. They saw the establishment of the empirical sciences, the industrial revolution, the first wave of feminism, the rise of imperialism and colonialism, all of which are still relevant in today’s society. Steffen Hantke argues:

“What makes the Victorian past so fascinating is its unique historical ability to reflect the present moment.” (Difference Engines and Other Infernal Devices: History According to Steampunk. Extrapolation 40:3 (1999): pp. 244-254)

For us, the nineteenth century represents a turning point – a time where things could have happened differently in ways we can only imagine with the benefit of hindsight. Peter Nicholls writes,

“Victorian London has come to stand for one of those turning points in history where things can go one way or the other, a turning point peculiarly relevant to sf itself. It was a city of industry, science and technology where the modern world was being born, and a claustrophobic city of nightmare where the cost of this growth was registered in filth and squalor. Dickens – the great original Steampunk writer who, though he did not write sf himself, stands at the head of several sf traditions – knew all this.” (John Clute & Peter Nicholls, The Encyclopaedia of Science Fiction, 1993 (London: Orbit, 1999): p. 1161).

I loved reading Dickens even before reaching my teens. By the time I sat down to write THE ETERNAL MACHINE, I’d read most of his novels at least once.

Two or three years ago, a little before I decided to get THE ETERNAL MACHINE professionally edited, I wanted to do something different with the genre. One of my early drafts was set in an unnamed fantasy world, but the worldbuilding was lacking, so I decided to flesh it out by moving it to an alternate reality in Sydney, Australia. I decided it needed a recognisable landmark, and the Sydney Harbour Bridge immediately sprang to mind. Yep, I know the bridge wasn’t built until the early 20th Century, but Steampunk is a genre of anachronisms, and in my novel, magic and science are equally valid disciplines. This made a very corrupted version of the bridge not only recognisable but also possible.

Next I needed a magic system that was not entirely smoke and mirrors. I already had the bare bones, but I wanted something inextricably linked to character and based on as much history as imagination. Therefore I put on my subversive writer’s hat. Or perhaps took a wild risk, because instead of basing my magic on science fictional history or folk magic or myth, I chose to playfully base it on a real life obscure metaphysical theory — The Monadology — devised in 1690 (published 1714) by the philosopher, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. This theory has more recently been argued by Eric Steinhart to be a description of virtual reality.

What I ended up with was an anachronism within an anachronism, or in other words, a 17th Century theory that describes a 20th Century concept set in a 19th Century alternate reality. I’m not going to try and explain it all here — and I’ll blog about it later — but the challenge was to cherry pick enough of the theory to eliminate the need for more than a few sentences of explanation, which I drip fed where the plot demanded.

Using this idea quickly became fun and most probably irreverent. If Leibniz or any professional philosophers would ever read it, I suspect they’d either be annoyed or amused 😉

The truth is: I discovered the Monadology twenty years ago, and have enjoyed reading about it ever since. Even papers that discredit its logic. After all, arguments for and against an idea are fodder for the muse, especially if that idea is controversial.

THE ETERNAL MACHINE ebook and paperback go live 14th January, 2022 worldwide including Amazon US Amazon AU Amazon UK Barnes & Noble Kobo US Kobo Au and Kobo UK

Unexpected Discoveries

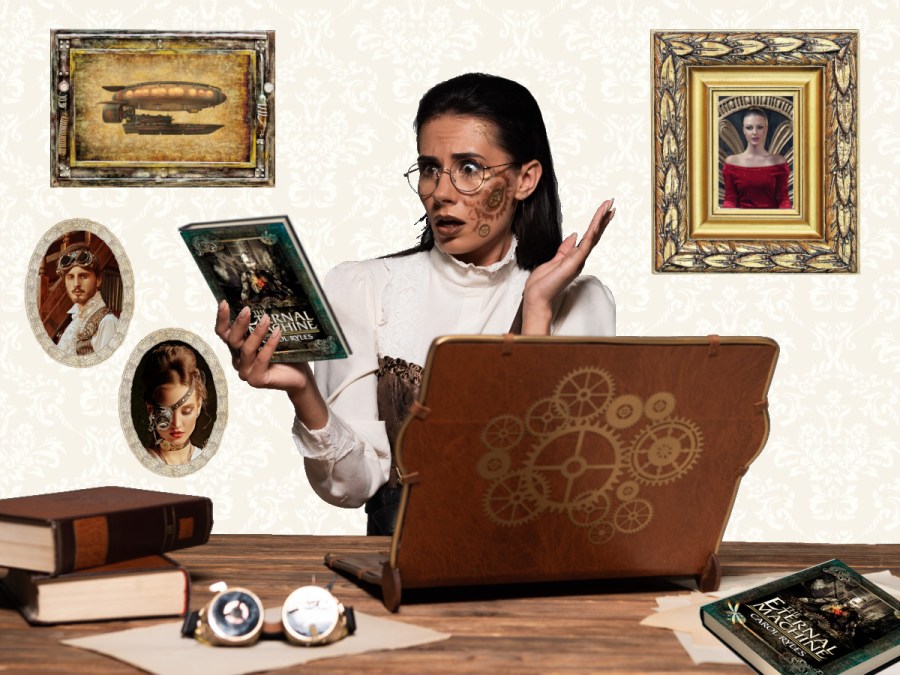

What does this image represent?

A. Me proofreading and spotting a typo?

B. A character learning that something is not as it seems?

C. A reader surprised by a plot twist?

Answer:

All of the above 😉

THE ETERNAL MACHINE ebook and paperback go live 14th January, 2022 worldwide including Amazon US Amazon AU Amazon UK Barnes & Noble Kobo US Kobo Au and Kobo UK

Video Credits:

In video

Feature Image Credits:

Worried woman sitting at table: LightField Studio

Damask Wallpaper No-longer-here

Oval Picture frame cut out from image by: Darkmoon_Art

Steampunk man’s and steampunk woman’s face in oval frames: Kiselev Andrey Valerevich

Framed steampunk airship: flutie8211

Gold Rectangular Picture Frame: Avantrend

Woman in Red dress: Avesun

Images edited by Carol Ryles using GIMP

Proofreading and Layouts

My second to last proofread has arrived, and after combing through it, I was delighted to find my proofreader found only a single typo I hadn’t already found myself. I’ve still got a month until release date and I’m not going to sit back and believe there aren’t any errors left because I’m sure typo gremlins live inside my keyboard. If I slack off now, they might start self-replicating 😉 Fortunately I have one more proofread yet to arrive from a friend who also edits for a living. It’s taking a while but it will be worth it. Only then will I believe my job is done, and can then dedicate more time to writing novel number two.

Just for fun, here are some of the things I’ve had to fix:

The usual spelling errors and missed words. Not that many, fortunately, but they’re gone now.

A few missed quotation marks

Three malapropisms:

Appraised instead of apprised

Wretched instead of retched

Torturous instead of tortuous

Argh! Why doesn’t my brain see these when I write them? I asked a couple of other writers around my age and they confirmed this is something that gets worse as people get older. Not happy about that. At least I know now, and will triple check next time.

While I was proofreading I also tweaked a handful of sentences that still felt a bit clunky. To be honest, I could probably keep doing that for the next 10 years, but now it’s time to stop.

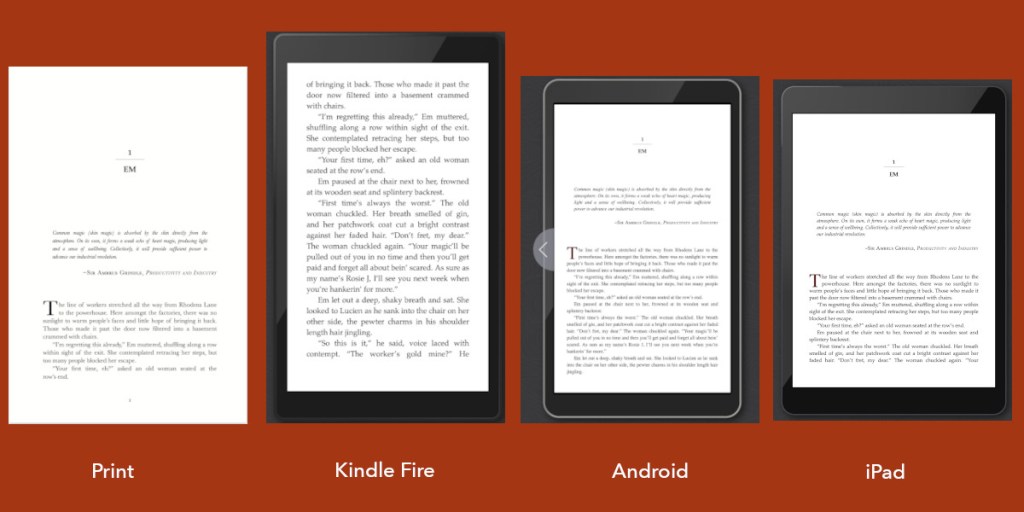

Lastly, I’ve been checking and double checking my layouts. Six months ago, I purchased Vellum, and it was expensive and only works on a Mac (which fortunately I have). It was easy to learn and certainly a worthwhile investment. Ebooks and Print layouts look way more professional than I could have done myself, and these are made within seconds with just a single keystroke.

Here are some examples of how my novel is going to look:

The beauty of doing the formatting myself with Vellum is that if I need to do any changes I can just get in there and do it and everything still looks great. It also does Nook, Kobo, Google and Generic.